Speaking Notes for Evan Siddall, President and Chief Executive Officer, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

Halifax Chamber of Commerce

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Check against delivery

Introduction

Thank you; good afternoon, and let me extend a special thank you to the Halifax Chamber of Commerce and the Nova Scotia Association of Realtors.

As President of CMHC, I am asked from time to time what keeps me awake at night. And one thing that’s been bothering me is how do I tell my 76-year-old mother that I need her help?

You see, I have a problem.

The problem is that my mother lives alone in a large, three-bedroom house in a suburb of Toronto – much more housing than she needs at this stage of life. Hers is a home, in fact, that would be better suited to a working family that truly needs all three bedrooms – a family that is now being forced further and further into suburbia to find suitable housing they can afford. That’s adding hours of commute time to their already stressed week, reducing their time with family and friends and diminishing their quality of life. There’s more but I will return to that shortly.

It seems unfair to lay the housing problems faced by one segment of society at the feet of another, especially seniors who have worked hard all their lives to give themselves the financial security and stability that comes with owning a home.

In fact, I’m not blaming anyone. My assertion is that unless we act purposefully, the current generation faces challenges that Baby Boomers did not. And we all deserve a place to call home.

The fact is that the situation I’ve described is real, it’s common in bigger cities across the country, and it’s contributing to housing market imbalances in those communities.

Here in Halifax, the story is different. Prices have not grown to the same extent as they have in Vancouver and Toronto. Nonetheless, the housing needs of seniors in this city are real and pressing. In the last installment of the National Household Survey,[1] about 45 per cent of Halifax renters over the age of 60 spent more than 30 per cent of their household income on shelter costs. The figure climbs to 55 per cent for those over 75. This stands in sharp contrast to owners of the same age group: only 15 per cent report shelter costs exceeding 30 per cent.

Percentage of Seniors in Halifax Spending More Than 30% of Household Income on Housing

| Age Group | Renters | Owners |

|---|---|---|

| 60 – 74 years | 58.1 | 41.89 |

| 75 years or older | 66.7 | 33.16 |

Statistics Canada, National Household Survey, 2011

My comments today will be at a more macro-economic level and in no way neglect seniors’ housing needs.

Housing: A unique investment

Housing is unfortunately widening the inequality gap in Canada. And Canadians’ propensity to view housing as a “can’t lose” investment is behind another potentially destabilizing phenomenon – the “wealth effect,” or increased consumer spending that occurs when high house prices make homeowners believe they are wealthier than they are.

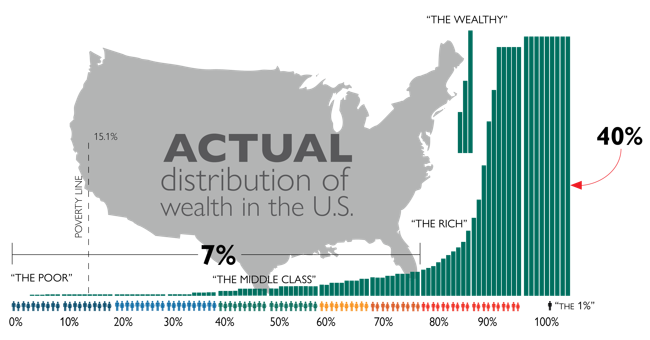

A visual from the YouTube video on “Wealth Inequality in America” showing that the top 1 per cent own 40 per cent of America’s wealth while the bottom 80 per cent hold only 7 per cent.

Artistic reproduction of chart from “Wealth Inequality in America” — YouTube

Canadians now have more options for saving and investing money than possibly ever before: RRSPs, RESPs, TFSAs, low-fee online brokerages that allow us to buy stocks, bonds or GICs at the click of a mouse. But for many, housing is still seen as a primary means of building wealth and financial security. The latest data from Statistics Canada suggest that principal residences account for $4.3 trillion of Canadians’ $12[.0] trillion of assets.[2]

The compulsion around housing security motivates the beneficial “forced savings” of mortgage payments. We know that Canadians will go to great lengths to make their mortgage payments – the arrears rate reported by the Canadian Bankers Association is less than a quarter of one per cent (0.24%).[3]

Percentage of Residential Mortgages in Arrears, Canada and U.S.

|

Year |

Canada: All Residential Mortgages |

U.S.: All Residential Mortgages |

U.S.: Prime Mortgages |

U.S.: Subprime Mortgages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2002 |

0.37 |

0.88 |

0.29 |

3.16 |

|

2003 |

0.33 |

0.89 |

0.30 |

3.23 |

|

2004 |

0.26 |

0.87 |

0.29 |

2.70 |

|

2005 |

0.27 |

0.90 |

0.32 |

2.59 |

|

2006 |

0.25 |

0.96 |

0.36 |

2.89 |

|

2007 |

0.26 |

1.22 |

0.49 |

4.32 |

|

2008 |

0.33 |

2.13 |

1.21 |

7.03 |

|

2009 |

0.45 |

4.13 |

2.85 |

12.58 |

|

2010 |

0.43 |

4.43 |

3.13 |

13.92 |

|

2011 |

0.38 |

3.45 |

2.19 |

10.97 |

|

2012 |

0.33 |

3.02 |

1.78 |

9.36 |

|

2013 |

0.31 |

2.63 |

1.43 |

9.35 |

|

2014 |

0.29 |

2.30 |

1.26 |

8.53 |

|

2015 |

0.27 |

1.81 |

1.03 |

6.65 |

|

2016 Q1 |

0.28 |

1.55 |

0.89 |

6.07 |

|

2016 Q2 |

0.28 |

1.47 |

0.83 |

5.82 |

|

2016 Q3 |

0.28 |

1.41 |

0.80 |

5.51 |

|

2016 Q4 |

0.28 |

1.60 |

1.07 |

5.53 |

|

2017 Q1 |

0.27 |

1.37 |

||

|

2017 Q2 |

0.25 |

1.20 |

||

|

2017 Q3 |

0.24 |

1.29 |

||

|

2017 Q4 |

0.24 |

1.72 |

Canadian and U.S. Residential Mortgage Arrears and Foreclosure Rates, 2002 – 2016 Q3

Many households have difficulty applying the same savings discipline to other savings options – and they often simply don’t have the money to invest vast sums in RRSPs or TFSAs, in part because too many are mortgage-poor, guarding the reliability of their mortgage payments.

While we can’t deduct our mortgage interest from taxes in Canada, tax-free gains and low interest rates make investing in our homes an irresistible means of savings. A home’s value can increase ten-fold or more without triggering capital gains tax. You will detect a pattern here: this benefit is greatest for higher-income households. Housing helps the rich get richer. Unless it doesn’t, of course …

Even if housing has been a reliable means of building wealth over the recent long term, experience in the U.S. and elsewhere demonstrated that banking on your home’s value only continuing to increase is foolhardy. The consequences of excessive housing investments are severe if house prices drop, particularly for those who are already stretched to their financial limits.

And because of the obvious linkages between mortgages and the banking industry, and between housing, personal savings and wealth, housing is deeply entwined in our broader economic well-being. For the benefit of our financial system, therefore, we have an obligation to ensure that Canadians have the awareness and information they need to make the right long-term decisions about housing – including an awareness of the risk of loss.

But there is something about housing. Many factors combine to attract us to owning our houses, some of which are quite emotional. I’ve been given to quoting from Matthew Desmond’s book, Evicted. He calls the home the “wellspring of personhood.” We call home ownership the “American dream” when the truth is that a place to call home is timeless. Charles Dickens said, “Home ... is a name, a word, it is a strong one; stronger than magician ever spoke, or spirit answered to, in strongest conjuration.”[4]

These psychological or behavioural factors give housing strange qualities as an investment vehicle. We know that houses are particularly prone to boom-bust cycles because of their odd combined characteristics as both consumables and investables. Couple that with the emotional investment people make in their homes, and residential real estate markets can be dangerous places for young, highly leveraged families. Housing markets are volatile, pervasive, illiquid and easy to make riskier through leverage. As I’ve said, this makes for a toxic brew. Of the 46 systemic banking crises for which house price data are available, more than two thirds were preceded by boom-bust patterns in house prices.[5]

Indeed, there is something about housing.

Trees do not grow to the sky

Worldwide, house prices have grown impressively since roughly the middle of the 20th Century.[6] Economic historians have also determined that, over the very long term, returns on housing match those of equities.[7] While such analysis does not take into account the costs of on-going maintenance and repairs, which people overlook but which reduce their rate of return,[8] housing has been a sound long-term investment.

Historic Growth of House Prices in Canada

| Year | Real House Price Index 1957 = 100 |

|---|---|

| 1921 | 32.1452156 |

| 1922 | 31.6049979 |

| 1923 | 32.4986478 |

| 1924 | 32.2687322 |

| 1925 | 31.2142595 |

| 1926 | 30.5854818 |

| 1927 | 30.9597608 |

| 1928 | 31.7614316 |

| 1929 | 32.8510731 |

| 1930 | 32.1813544 |

| 1931 | 33.0868419 |

| 1932 | 32.7936781 |

| 1933 | 32.9939578 |

| 1934 | 33.4685166 |

| 1935 | 32.581754 |

| 1936 | 32.9082231 |

| 1937 | 33.8818681 |

| 1938 | 32.9494776 |

| 1939 | 33.1299402 |

| 1940 | 33.8416399 |

| 1941 | 35.4474703 |

| 1942 | 37.0681623 |

| 1943 | 39.0750159 |

| 1944 | 40.4907353 |

| 1945 | 40.994615 |

| 1946 | 43.0419489 |

| 1947 | 44.0702712 |

| 1948 | 44.4934815 |

| 1949 | 45.5594306 |

| 1950 | |

| 1951 | |

| 1952 | |

| 1953 | |

| 1954 | |

| 1955 | |

| 1956 | 97.1155282 |

| 1957 | 100 |

| 1958 | 105.306602 |

| 1959 | 107.532167 |

| 1960 | 105.980298 |

| 1961 | 104.195071 |

| 1962 | 104.166218 |

| 1963 | 103.713733 |

| 1964 | 106.363676 |

| 1965 | 109.710657 |

| 1966 | 116.035097 |

| 1967 | 122.264878 |

| 1968 | 131.022945 |

| 1969 | 136.569789 |

| 1970 | 133.343252 |

| 1971 | 136.191543 |

| 1972 | 140.621835 |

| 1973 | 158.514161 |

| 1974 | 181.460792 |

| 1975 | 188.473407 |

| 1976 | 189.173389 |

| 1977 | 181.95275 |

| 1978 | 173.113181 |

| 1979 | 170.704874 |

| 1980 | 176.390238 |

| 1981 | 177.840624 |

| 1982 | 152.784394 |

| 1983 | 153.013328 |

| 1984 | 145.894522 |

| 1985 | 147.58405 |

| 1986 | 165.963769 |

| 1987 | 186.018822 |

| 1988 | 210.942243 |

| 1989 | 227.539333 |

| 1990 | 209.734156 |

| 1991 | 207.721153 |

| 1992 | 206.592673 |

| 1993 | 206.847599 |

| 1994 | 213.379746 |

| 1995 | 199.25921 |

| 1996 | 196.553817 |

| 1997 | 198.067755 |

| 1998 | 193.265383 |

| 1999 | 197.141394 |

| 2000 | 199.517792 |

| 2001 | 203.57282 |

| 2002 | 218.692841 |

| 2003 | 233.37353 |

| 2004 | 250.193163 |

| 2005 | 269.747223 |

| 2006 | 294.179282 |

| 2007 | 318.873468 |

| 2008 | 309.383705 |

| 2009 | 324.919584 |

| 2010 | 337.799893 |

| 2011 | 350.212664 |

| 2012 | 346.046196 |

| 2013 | 361.134466 |

| 2014 | 377.746645 |

| 2015 | 405.297333 |

| 2016 | 442.350417 |

*Data not available for this period

Source: Statistics Canada, CMHC, CREA.

It is a law of investing that past results are poor predictors of the future. Yet, many Canadians believe house prices don’t fall and use that belief as a financial planning assumption. We asked people who had just bought a home in Montréal, Toronto or Vancouver if they thought real estate was the best long-term investment.[9] More than three quarters of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed. People believe trees grow to the sky. Only half agreed or strongly agreed that financial investments – stocks and bonds – were the best option in the long term.

Percentage of Respondents of CMHC's 2017 Homebuyers' Motivations Survey Who Agree or Strongly Agree That Real Estate or Financial Investment is the Best Long-Term Investment

| City | Real estate is the best long-term investment in your city | Financial investment is the best long-term investment |

|---|---|---|

| Vancouver | 75.8 | 46.5 |

| Toronto | 79.7 | 53.1 |

| Montréal | 80.4 | 55.2 |

Source: Homebuyers' Motivations Survey 2017

CMHC Homebuyers Survey 2017

In response to a separate question, around 70 per cent of respondents in Vancouver and Toronto told us that future growth in the value of their home was important or very important to them, compared to 60 per cent in Montréal, where there is a higher tendency to rent and price increases have been smaller. So we know that many homebuyers make decisions to purchase or sell a house with an eye to the future. In short, they are willing to pay more for housing today in anticipation of price gains tomorrow. The more optimistic they are, the more they are willing to bid up prices. Excessive optimism about the future of house prices can lead to speculative investment and bidding wars, both of which further drive price escalation.

And for these 15 major Canadian cities (see graphics below), it now takes an average of 170 hours of work per month to own a house at less than 30 per cent of our gross income (155 hours in Halifax) ... and an average of about 138 hours of work to rent a home without spending more than 30 per cent of our income (148 hours in Halifax).

Large Canadian cities listed by number of hours a person earning the average hourly wage would need to work in a month so that mortgage payments do not exceed 30% of gross income

| City | Hours |

|---|---|

| Vancouver | 262 |

| Toronto | 244 |

| Victoria | 220 |

| Hamilton | 189 |

| Regina | 173 |

| Calgary | 167 |

| Edmonton | 166 |

| Saskatoon | 159 |

| Halifax | 155 |

| Winnipeg | 151 |

| St. John's | 151 |

| Montréal | 146 |

| Ottawa – Gatineau* | 133 |

| Moncton | 127 |

| Québec | 113 |

*Includes both the Ontario and Quebec portions of Ottawa – Gatineau

Source: Equifax data for mortgages opened in Q2 – 2017, and Statistics Canada for average weekly earnings. CMHC calculations. Average hourly earnings = average weekly earnings/40, and number of hours needed to pay monthly mortgage = Average monthly mortgage payment/0.3/ average hourly earnings. Number of hours needed to work in a month to ensure that no more than 30% of gross income is spent on shelter.

Large Canadian cities listed by number of hours a person earning the average hourly wage would need to work in a month so that rent payments do not exceed 30% of gross income

| City | Hours |

|---|---|

| Vancouver | 204 |

| Toronto | 175 |

| Victoria | 166 |

| Winnipeg | 156 |

| Halifax | 154 |

| Calgary | 136 |

| Saskatoon | 134 |

| Edmonton | 135 |

| Ottawa* | 138 |

| Hamilton | 140 |

| Regina | 132 |

| St. John's | 124 |

| Moncton | 122 |

| Québec | 109 |

| Montréal | 106 |

*Not Ottawa-Gatineau

Source: CMHC Rental Market Survey 2017 for average 2 bedroom rent, and Statistics Canada for average weekly earnings. CMHC calculations. Average hourly earnings = average weekly earnings/40, and number of hours needed to pay monthly rent = Average rent/0.3/ average hourly earnings. Number of hours needed to work in a month to ensure that no more than 30% of gross income is spent on shelter.

Trees don’t grow to the sky. It is worth asking if housing will continue to be the reliable means of saving that Canadians have come to expect as our cities continue to grow and change in the years ahead.

Long-term implications

To get back to my mother, it’s important to ask who has reaped the rewards of housing value gains and to set the answer within a broader socioeconomic context.

Writing in the early 19th Century, the English economist David Ricardo theorized that the combination of a limited supply of land and a growing population would lead to higher land prices – accruing what he called “economic rents” to landowners.[10] Indeed, most of the increase in home prices over the past few decades have been accounted for by increases in the price of land. Two hundred years later, economists David Miles and James Sefton approached the issue from a slightly different perspective, arguing that house prices are likely to continue to increase unless – among other factors – housing density is increased.[11]

As I have noted elsewhere, most urban Canadians support the concept of densification – as long as it is happening in someone else’s neighbourhood.[12] But it can’t always happen somewhere else. It needs to happen in every community where housing markets are imbalanced due to a lack of supply, or where urban sprawl is impacting our environment and quality of life. While you might think that these dynamics do not apply to Halifax, it’s still worth noting that this is one of the least densely populated cities in Canada.

The alternative to densification is far more worrisome than whether the character of a neighbourhood may change a bit. Continued escalation of house prices in Canada will lead only to higher household debt, reduced housing affordability in both homeownership and rental markets, unsustainable urban growth and rising wealth inequality – an even greater gap between the rich and the poor in this country.[13]

Income Inequality: The Gini Coefficient in Canada and Various Canadian Cities, 1995 – 2013

| Year | Canada | Vancouver (B.C.) | Toronto (ON) | Halifax (N.S.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 0.638 | 0.635 | 0.645 | 0.603 |

| 1996 | 0.643 | 0.640 | 0.653 | 0.612 |

| 1997 | 0.645 | 0.642 | 0.657 | 0.616 |

| 1998 | 0.645 | 0.644 | 0.655 | 0.617 |

| 1999 | 0.644 | 0.648 | 0.653 | 0.612 |

| 2000 | 0.646 | 0.653 | 0.660 | 0.612 |

| 2001 | 0.643 | 0.647 | 0.657 | 0.609 |

| 2002 | 0.644 | 0.653 | 0.661 | 0.613 |

| 2003 | 0.646 | 0.658 | 0.665 | 0.614 |

| 2004 | 0.647 | 0.663 | 0.667 | 0.616 |

| 2005 | 0.648 | 0.660 | 0.669 | 0.614 |

| 2006 | 0.650 | 0.659 | 0.675 | 0.612 |

| 2007 | 0.648 | 0.653 | 0.671 | 0.609 |

| 2008 | 0.646 | 0.645 | 0.668 | 0.610 |

| 2009 | 0.649 | 0.651 | 0.671 | 0.612 |

| 2010 | 0.652 | 0.661 | 0.675 | 0.610 |

| 2011 | 0.650 | 0.661 | 0.674 | 0.615 |

| 2012 | 0.649 | 0.656 | 0.672 | 0.615 |

| 2013 | 0.650 | 0.656 | 0.672 | 0.620 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Income Statistics Division

GINI, Individual Earnings (sum of employment income, self-employment income, and other employment income), by province and CMA, LAD

One of the cornerstones of our society is intergenerational income mobility: the notion that people can improve their social and economic status from one generation of a family to the next. While intergenerational mobility is substantially higher in Canada than in the U.S., recent evidence suggests that it is not as strong here as previously believed. Nor is intergenerational income mobility available for all.[14]

Housing threatens to buttress these barriers. A slowdown or reversal in the trend line of house prices will impact generations differently. And a lack of affordable housing in our cities restricts access to better-paying jobs for those who want to move there. Older owners can help. For example, young people who were brought up in these communities may benefit from staying at home with their parents to save for a down payment.[15] Older owners could also help by not impeding new supply, by actively resisting densification in their neighbourhoods, for example.

Housing as a drag on economic growth

The “wealth effect” I mentioned earlier has also become an important issue in understanding macroeconomic trends. As house prices rise, those who are not readily able to borrow to increase consumer spending – perhaps because of poor credit – may instead withdraw equity from their home by incurring debt, for example through a line of credit or second mortgage.[16] This group is also more likely to reduce consumption if house prices drop. A study in Australia found that young people with low and medium levels of liquid wealth tend to be sensitive to home prices, as are older Australians whose net worth is largely tied up in housing.[17] U.S. researchers also found that “young people who are more likely to be credit-constrained, and older homeowners, likely to be ‘trading down’ on their housing stock, experience the largest housing wealth effects.”[18] Again, therefore, the young could suffer disproportionately if they become homeowners and prices subsequently fall.

The negative effect of falling house prices on consumption can last a long time, as suggested by the U.S. experience after the Great Recession.[19] Consequently, if rising home prices create perceptions of greater wealth that eventually prove to be unfounded, the related increase in consumption will be unsustainable. The impacts on financial stability may be particularly severe if that consumption is financed by other credit. Economists Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, as well as colleagues at the IMF, have shown that high levels of indebtedness coupled with elevated house prices precede economic contractions. They call the relationship “so robust as to be as close to an empirical law as it gets in macroeconomics.”[20]

Too much housing?

Since housing represents such an important part of household wealth, homeowners tend to maintain their homes in a state of good repair. Home renovations also tend to increase value. Neither of these activities should be discouraged: they are good for housing markets and for local economies. Regrettably, another way homeowners seek to preserve the value of their properties is by discouraging increased housing supply in their communities, for fear that this could lead to a decline in home prices. Unduly restricting supply may sow the seeds of a decline in the housing market by driving unsustainable price increases, leading to housing bubbles and financial instability, and a subsequent crash.

While housing has provided an attractive return on investment for Canadians trying to build their wealth, there are economic trade-offs. For the homeowner, the lack of diversification from putting most of their wealth in a single asset class – housing – represents a significant risk. For the country as a whole, dollars that are tied up in housing, often for decades, are not available for other productive investments that fuel long-term economic growth: investments in new technologies, skills, innovation and productivity improvements. And with housing comprising a proportion of GDP that is too high, it is becoming the drag on economic growth economists predict it to be.

Housing is mining our economic future.

Ratio of Ownership Transfer Costs to Business Research and Development Spending*

| Year | USA | Canada |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 0.90566094 | 0.78361626 |

| 1996 | 0.92265638 | 0.96578273 |

| 1997 | 0.92535628 | 0.86517284 |

| 1998 | 1.02409786 | 0.72373632 |

| 1999 | 1.0089164 | 0.73929434 |

| 2000 | 0.92045614 | 0.64059621 |

| 2001 | 0.9925124 | 0.64280509 |

| 2002 | 1.19796289 | 0.81547355 |

| 2003 | 1.38056154 | 0.8713544 |

| 2004 | 1.59022649 | 0.94874629 |

| 2005 | 1.67908998 | 1.05096258 |

| 2006 | 1.42079161 | 1.10013898 |

| 2007 | 1.08251779 | 1.25675162 |

| 2008 | 0.68016896 | 1.07067666 |

| 2009 | 0.61180763 | 1.22520309 |

| 2010 | 0.60325124 | 1.31505956 |

| 2011 | 0.57611137 | 1.37951992 |

| 2012 | 0.64343805 | 1.41445903 |

| 2013 | 0.71826934 | 1.52203115 |

| 2014 | 0.68672863 | 1.69932453 |

| 2015 | 2.00011469 | |

| 2016 | 2.21888779 | |

| 2.21540517 |

*Index: 1994 = 1

Sources: Statistics Canada, Bureau of Economic Analysis

Housing, wealth and the need for supply

Our recent report on escalating home prices in major urban centres pointed to increasing levels of wealth in Toronto contributing to house price increases by driving up the prices of more expensive single-detached housing.[21] This should strike us as un-Canadian: we are a country that is proudly inclusive with citizens who are socioeconomically mobile. I will add that our study also determined that a weak and lagging supply response was a major factor contributing to unsustainable house price increases in both Toronto and Vancouver.

Unrealistic expectations of trees in the clouds can be confronted by data on housing supply today. Improved market information can therefore help limit unwarranted price increases. If prospective homebuyers know that additional supply is on the horizon, they will be less likely to pay exorbitant prices for homes that are currently available – and in high demand – in a supply-restricted market. Moreover, purely financial investors will be discouraged by pending supply.

Federal policy makers recognize that supply is a big part of the housing affordability challenge in Toronto, Vancouver and many other communities across the country – both large and small. That’s why the Government of Canada’s 10-year, $40 billion National Housing Strategy unveiled last fall is unapologetically a supply-oriented plan.

We believe that supply needs to be increased across the housing spectrum – from homeless shelters to high-end single family homes and condos. However, the National Housing Strategy focuses first on vulnerable Canadians who most need our help. Ensuring they have a roof over their heads is a crucial step in giving them the opportunity to be fully included in our society and succeed.[22] And increasing the supply of affordable rental housing will have the added benefit of off-setting increasing levels of demand for homeownership, which as I have previously said just drives home prices upward.

Ratio of Ownership Transfer Costs to Business Research and Development Spending*

| Year | USA | Canada |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 0.90566094 | 0.78361626 |

| 1996 | 0.92265638 | 0.96578273 |

| 1997 | 0.92535628 | 0.86517284 |

| 1998 | 1.02409786 | 0.72373632 |

| 1999 | 1.0089164 | 0.73929434 |

| 2000 | 0.92045614 | 0.64059621 |

| 2001 | 0.9925124 | 0.64280509 |

| 2002 | 1.19796289 | 0.81547355 |

| 2003 | 1.38056154 | 0.8713544 |

| 2004 | 1.59022649 | 0.94874629 |

| 2005 | 1.67908998 | 1.05096258 |

| 2006 | 1.42079161 | 1.10013898 |

| 2007 | 1.08251779 | 1.25675162 |

| 2008 | 0.68016896 | 1.07067666 |

| 2009 | 0.61180763 | 1.22520309 |

| 2010 | 0.60325124 | 1.31505956 |

| 2011 | 0.57611137 | 1.37951992 |

| 2012 | 0.64343805 | 1.41445903 |

| 2013 | 0.71826934 | 1.52203115 |

| 2014 | 0.68672863 | 1.69932453 |

| 2015 | 2.00011469 | |

| 2016 | 2.21888779 | |

| 2.21540517 |

I spoke earlier of the danger of heightened expectations. Constrained supply further aggravates this phenomenon. Harvard housing economist Ed Glaeser has found a systematic behavioural pattern whereby homebuyers fail to understand the supply response when house prices increase and then attract speculators.[23] The failure to anticipate a supply response means that housing is seen as a one-way bet, that house prices have nowhere to go but up, which leads to a “fear of missing out.” Unrealistic expectations of house price gains mean that homebuyers are more willing to pay higher prices today, and an unsustainable cycle feeds on itself. The risk of speculators entering the market is also greater when supply is seen as unresponsive.[24]

Again, trees just don’t grow to the sky. Developing greater transparency on future housing supply is an important means of keeping expectations in check. Clearly this is a difficult task and fraught with uncertainty, but having some ranges of scenarios is better than none. CMHC will do our part to increase the scope and availability of this information in Canada. On our own and via our partnership with StatsCan, we have a plan to substantially improve the availability and accessibility of housing market data in Canada.

Intergenerational rebalancing

Returning again to my dear mother, she and my father bought the house I grew up in in 1967 for $22,900. Today that house is probably worth more than $700,000. Mom doesn’t own it any more – she has since bought another home – but that’s a 16 per cent compounded pre-tax return over 50 years. Try to beat that.

Baby Boomers in Canada have had a pretty sweet deal, historically speaking. Economically, they have experienced historic growth, government deficit spending, pension entitlements that have not always been fully funded and near-uninterrupted house price growth. In many ways, they have been borrowing from the generations that follow. And the borrowing goes beyond that: environmentally in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and carbon consumption, comparatively low levels of foreign aid and charitable giving.

None of this was intended so I’m not assigning blame; in fact, I am encouraging solutions that involve them. If not, we will face unhelpful social pressures.

Chuck Palahniuk wrote pointedly about the inter-generational angst of Generation X in his nihilistic novel, Fight Club:

“We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war… our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

This imbalance does indeed have menacing seeds within it. Not to sound like the Peter Pan of Canadian housing but the young need affordable housing, too. There is comfort and dignity in having a place to call home. Baby Boomers’ wealth has been built to some extent on the backs of their children and grandchildren. And again, the burden of recent mortgage insurance parameter changes have fallen on the young: on first-time home buyers.

We shouldn’t be afraid to call for an intergenerational accounting. Low interest rates help: they entail an implicit transfer from older savers to younger borrowers. In the U.K., the Resolution Foundation recently called for a wealth tax to redress similar inequities there.[25]

Borrowing from the “Bank of Mom and Dad” at favourable rates is a means by which individual families can rebalance. In January, CMHC made it easier for relatives to pass on their homes to the next generation: mom and dad can now gift equity that they have built up in their home to a child in place of a down payment. I’d like to explore how we can use the mortgage insurance regime to reward this kind of support further, if we can do so without contributing to affordability problems.

Reverse mortgages, which allow senior homeowners to convert part of the equity in their homes into cash, are fraught with potential abuses; used responsibly, however, they may offer another vehicle to help first-time homebuyers. We support “aging in place” but it’s worth us questioning how policies can result in over-housing. It is regressive for my mother to be so over-housed when we are desperate for supply in the Greater Toronto Area.

However, secondary suites or basement apartments are a source of new housing that seniors (or others) can use and which may help affordability, too. Seniors can age in place and still help address these challenges.

I’m not calling for ageism, nor discrimination. And I need to acknowledge the acute problem of poverty among seniors. However, we are left with few sources of funds to solve our housing challenges. Aging Baby Boomers may be sitting on some answers. Like I said, we need their help.

Oh, and one more thing: Mom, I know you’re going to read this speech. And you will send it all of your friends, which is sweet of you. Firstly, I’m sorry for picking on you. Secondly, if and when you sell your home is your business, not mine. And, last, don’t worry: my fight club days are over.

[1] Statistics Canada, 2016. 2011 National Household Survey, 2011 Census Program.

[2] Statistics Canada, 2017. Survey of Financial Security, 2016, The Daily, 7 June 2017.

[3] Canadian Bankers Association, 2018. Number of Residential Mortgages in Arrears, 31 January 2018.

[4] Charles Dickens. The Life and Times of Martin Chuzzlewitt, serially published between 1842 and 1844.

[5] Christopher Crowe, Giovanni Dell'Ariccia, Deniz Igan and Paul Rabanal, 2011. “How to Deal with Real Estate Booms: Lessons from Country Experiences,” IMF Working Paper, April 2011.

[6] Katharina Knoll, Moritz Schularick and Thomas Steger, 2017. “No Place Like Home: Global House Prices, 1870-2012,” American Economic Review, Vol. 107, No. 2, February, pp. 331-353.

[7] Òscar Jordá, Katharina Knoll, Dmrity Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick and Alan M. Taylor, 2017. “The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870-2015,” Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper, DP12509, December.

[8] Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Saunton, 2018. “Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2018,” Credit Suisse, February.

[9] Our survey was inspired by a similar survey undertaken in the U.S. by Robert Shiller, one of the founding fathers of behavioural economics, a relatively new field of study that aims to understand behaviours as they actually occur, rather than how people should behave in theory. We know that Canadians are generally not saving enough to secure their financial future. Behavioural economics can help explain why, and hopefully lead to practical responses to encourage savings. Some of this work is summarized in Karl E. Case, Robert J. Shiller and Anne K. Thompson, 2012. “What Have They Been Thinking? Homebuyer Behavior in Hot and Cold Markets,” Brookings Papers in Economic Activity, Fall, pp. 265-315.

[10] David Ricardo, 1817. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, London: John Murray. These issues are examined theoretically in Volker Grossman and Thomas Steger, 2017, “Das House-Kapital: A Long Term Housing & Macro Model,” IMF Working Paper WP/17/80.

[11] David K. Miles and James Sefton, 2017. “Houses across time and across place” Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper, DP12103, June.

[12] Evan Siddall, 2018. “It Takes a Village to Build a City: Housing Affordability as a Shared Responsibility,” speech to the, Northwind Professional Institute Housing Finance Forum, Cambridge, Ontario, 7 February 2018.

[13] Matthew Rognlie, 2015. “Deciphering the Fall and Rise in the Net Capital Share: Accumulation or Scarcity?,” Brookings Paper on Economic Activity, Spring, pp. 1-69.

[14] Wen-Hao Chen, Yuri Ostrovsky and Patrizio Piraino, 2016. “Economic Insights: Intergenerational Income Mobility: New Evidence from Canada,” Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016.

[15] Wen-Hao Chen, Yuri Ostrovsky and Patrizio Piraino, 2016. “Economic Insights: Intergenerational Income Mobility: New Evidence from Canada,” Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

[16] Matteo Iacoviello, 2011. “Housing Wealth and Consumption,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, International Finance Discussion Papers, Number 1027. An example of this type of analysis is Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, 2011. “House Prices, Home Equity-Based Borrowing and U.S. Household Leverage,” American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 5, August, pp. 2132-2156.

[17] Konark Saxena and Peng Wang, 2017. “How Do House Prices Affect Household Consumption Growth Over the Life Cycle?,” mimeo, UNSW Business School.

[18] Charles W. Calomiris, Stanley D. Longhofer and William Miles, 2012. “The Housing Wealth Effect: The Crucial Roles of Demographics, Wealth Distribution and Wealth Shares,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 17740, January 2012.

[19] Greg Kaplan, Kurt Mitman and Giovanni L. Violante, 2017. “The Housing Boom and Bust: Model Meets Evidence,” mimeo, University of Chicago.

[20] Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, 2014. House of Debt: How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again, University of Chicago Press, 2014.

[21] CMHC, Market Analysis Centre, 2018. Examining Escalating House Prices in Large Canadian Metropolitan Centres, February 2018.

[22] Evan Siddall, 2015. “Why Housing Matters,” speech to the Board of Trade of Metropolitan Montréal, 3 December 2015; and Evan Siddall, 2017. “No Solitudes: A Canadian National Housing Strategy,” speech to the Canadian Club of Toronto, 1 June 2017.

[23] Edward L. Glaeser, 2013. “A Nation of Gamblers: Real Estate Speculation and American History,” American Economic Review, Vol. 103, No. 3, May 2013, pp. 1-42.

[24] Stephen Malpezzi and Susan M. Wachter, 2005. “The role of speculation in real estate cycles,” Journal of Real Estate Literature 13, 143-164, 2005.

[25] David Willetts, 2018. “Baby boomers are going to have to pay more tax on their wealth to fund health and social care,” The Resolution Foundation, 5 March 2018.

Share via Email

Share via Email